Code

# Load metadata and summary statistics

metadata <- readRDS(here("blog", "Gbif Kenya", "data", "processed", "metadata.rds"))

summary_stats <- readRDS(here("blog", "Gbif Kenya", "data", "processed", "summary_stats.rds"))Kwizera Jean

November 25, 2025

IMPORTANT NOTICE: This document represents an independent analysis conducted to satisfy scientific curiosity and advance biodiversity data science methods. It has not undergone formal peer review and should not be cited as a peer-reviewed publication. While the methods employed follow established scientific standards and best practices in biodiversity informatics, the findings and interpretations presented here are preliminary and subject to revision. This work is shared openly to:

Users of this analysis should exercise appropriate scientific judgment and consider conducting additional validation for critical applications. Feedback, suggestions, and collaborative refinement of these methods are welcome.

Main Tables

Interactive Figures 🎯

Appendix Figures 📊

Background: Large observational datasets—from biodiversity records to public health surveillance—face common challenges of data quality issues and systematic sampling biases that can affect research conclusions and evidence-based decisions. Despite widespread recognition of these issues, most studies lack comprehensive documentation of quality problems and fail to systematically assess multi-dimensional biases. We present a general framework for data quality assessment and cleaning, demonstrated through application to Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) occurrence data from Kenya.

Framework Objectives: We developed and demonstrate a comprehensive framework for assessing and documenting data quality issues and systematic biases in large observational datasets. The framework emphasizes: (1) systematic flagging of quality issues without automatic removal, (2) transparent documentation of filtering decisions for each analysis, (3) multi-dimensional bias assessment (spatial, temporal, categorical), (4) sensitivity analysis comparing filtering strategies, and (5) complete reproducibility. While demonstrated using biodiversity data, the framework principles and methods are transferable to other observational data domains.

Methods: We downloaded 4,987,869 occurrence records from GBIF for Kenya and implemented a systematic quality flagging framework that identified and documented seven major quality issues: missing coordinates, high coordinate uncertainty (>10 km), inappropriate basis of record, missing species identification, invalid dates, duplicates, and coordinate quality flags. Critically, our approach flags quality issues rather than automatically removing records, allowing each downstream analysis to apply filters appropriate to its specific requirements. We assessed spatial bias using grid-based analyses, environmental space coverage, and spatial autocorrelation. Temporal bias was evaluated through trend analyses and completeness metrics. Taxonomic bias was quantified using diversity indices and species accumulation curves. We used generalized linear models (GLMs) and generalized additive models (GAMs) to identify environmental and geographic predictors of sampling effort.

Results: Data quality assessment identified issues in 2,728,482 records (54.7%), with coordinate-related problems being most common: 641,335 records (12.9%) flagged by CoordinateCleaner tests. Different analyses applied different quality filters based on their requirements: spatial bias analysis required valid coordinates and species identification but retained records near cities (the bias being measured); temporal analysis required valid dates but not coordinates; taxonomic analysis required only species identification. Under a moderate filtering strategy (coordinates, species, dates, no coordinate errors), 3,841,122 records (77%) were retained. Our bias analyses revealed significant spatial, temporal, and taxonomic biases. Sampling effort was concentrated near major cities and roads, with strong positive spatial autocorrelation (Moran’s I = 0, p < 0.001). Temporal analysis showed increasing trends in data collection, with 2.14 coefficient of variation in annual records. Taxonomic coverage was highly uneven, with a Gini coefficient of 0.966 for records across classes.

Conclusions: This framework addresses critical gaps in data quality documentation and bias assessment for large observational datasets. The Kenya biodiversity case study demonstrates: (1) how systematic flagging enables flexible, analysis-appropriate filtering rather than one-size-fits-all cleaning; (2) how multi-dimensional bias assessment reveals patterns that single-dimension analyses would miss; (3) how sensitivity analysis quantifies the impact of different quality control decisions; and (4) how complete documentation enables reproducibility and adaptation. While demonstrated with biodiversity occurrence data, the framework provides a methodological template applicable across observational data domains—from epidemiological surveillance to environmental monitoring to citizen science. The complete R implementation, with extensive documentation and educational features, serves as both a practical toolkit and a teaching resource for modern data science practices.

Keywords: data quality, data cleaning, observational data, sampling bias, reproducible research, GBIF, biodiversity data, Kenya, spatial bias, temporal bias, bias assessment

Large observational datasets—whether biodiversity records, public health surveillance, environmental monitoring, or citizen science observations—face common challenges that affect their utility for research and decision-making. This document presents a comprehensive framework for data quality assessment and cleaning demonstrated through application to biodiversity occurrence data. While our case study uses Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) data from Kenya (over 2 billion records globally; GBIF (2023)), the methods, workflows, and principles apply broadly to any large observational dataset with spatial, temporal, and categorical dimensions.

The fundamental challenge is that the utility of observational data depends on both data quality (accuracy and completeness of individual records) and representativeness (whether sampling patterns introduce systematic biases). These issues are universal across observational data domains, not unique to biodiversity informatics (Meyer et al. 2016).

Large observational datasets typically face two distinct but interconnected challenges:

Data Quality Issues include technical errors and inconsistencies such as missing coordinates, erroneous locations, incomplete categorical information, temporal inconsistencies, and duplicate records (Zizka et al. 2019). These issues are common across observational datasets and arise from: - Historical data digitization with incomplete metadata - Georeferencing errors when converting text descriptions to coordinates (biodiversity, disease surveillance) - Category revisions that create outdated classifications (taxonomy, disease codes, demographic categories) - Data entry mistakes during transcription or digitization - Multiple data sources sharing the same observations, creating duplicates - Sensor or measurement errors in automated recording systems

Systematic Biases stem from non-random observation patterns that create uneven coverage across space, time, and categories (Beck et al. 2014, Hortal et al. 2015). Unlike quality issues (which are errors), biases reflect real patterns in where, when, and what gets observed or sampled: - Spatial bias: Observations concentrated in accessible areas (near roads, cities, facilities) - Temporal bias: Changing observation intensity over time (often increasing with technology adoption) - Categorical bias: Focus on certain categories (charismatic species, common diseases, specific demographics) - Methodological bias: Different detection methods with varying efficiency - Reporting bias: Differential likelihood of reporting certain observations

Both quality issues and systematic biases can substantially affect downstream analyses if not properly addressed. Quality issues introduce noise and errors, while biases create misleading patterns that can be mistaken for real signals. For example, in biodiversity data, high species richness near cities might reflect sampling effort rather than true ecological patterns; in health surveillance, disease prevalence near hospitals might reflect testing availability rather than true epidemiology.

This framework is demonstrated using GBIF biodiversity occurrence data from Kenya, which serves as an ideal case study for several reasons:

Representative Challenges: Kenya’s biodiversity data exhibit common issues found in many large observational datasets: - Historical records with incomplete metadata alongside modern high-precision observations - Sampling concentrated in accessible areas (cities, roads, research stations) - Uneven temporal coverage reflecting changing research priorities and technologies - Taxonomic focus on certain groups (birds, large mammals) with limited coverage of others

Practical Importance: Beyond demonstrating the framework, this assessment has real-world value for Kenya: 1. The country hosts numerous endemic and threatened species requiring evidence-based conservation 2. Climate change impacts on East African biodiversity need robust baseline data assessment 3. Conservation planning and protected area management depend on understanding data limitations 4. National biodiversity monitoring and reporting obligations require reliable data sources

Transferability: The methods demonstrated here—quality flag documentation, multi-dimensional bias assessment, sensitivity analysis, and flexible filtering strategies—can be directly adapted to other contexts such as disease surveillance systems, environmental sensor networks, citizen science platforms, or social survey data.

A common problem across research domains is inadequate documentation of data cleaning procedures. Studies typically report only the final cleaned dataset size (e.g., “After quality control, 500,000 records remained”), without specifying: - What specific quality issues were identified and in how many records - What percentage of records had location errors, missing information, or duplicates - Which quality issues were filtered out vs. flagged for attention - Whether different analyses used different filtering strategies - Whether systematic biases were assessed and how they might affect conclusions

Furthermore, many studies apply a single, strict filtering strategy to all analyses, potentially: - Removing the signal: Filtering out the very patterns that should be studied (e.g., removing urban observations when studying accessibility bias) - Unnecessary data loss: Discarding records that would be valid for certain analyses (e.g., records without coordinates can still contribute to temporal or categorical assessments) - Over-filtering: Applying unnecessarily strict standards that reduce statistical power without improving analysis quality

This lack of flexibility and transparency makes it difficult to: - Assess whether quality standards were appropriate for each specific analysis - Compare data quality across datasets, regions, or categories - Evaluate fitness-for-use for different research questions - Replicate cleaning procedures in other studies - Identify systemic issues that data providers could address - Conduct sensitivity analyses to test robustness of conclusions

Need for a Comprehensive Framework: What’s needed is a systematic approach that: 1. Documents all quality issues without automatically removing records 2. Provides flexible filtering appropriate to each analysis 3. Assesses biases systematically across multiple dimensions 4. Enables transparency, reproducibility, and sensitivity testing

This work presents a comprehensive framework for data quality assessment and cleaning that addresses the documentation gap through:

1. Systematic Quality Flagging: Rather than immediately removing problematic records, we flag all quality issues, document their frequency and patterns, and then apply filters appropriate to each specific analysis.

2. Multi-Dimensional Bias Assessment: Systematic evaluation across spatial, temporal, and categorical dimensions using established statistical methods (spatial autocorrelation, trend analysis, diversity indices, predictive modeling).

3. Flexible Filtering Strategies: Different analyses require different quality standards. We document which filters are applied for each analysis and why, enabling transparency and sensitivity testing.

4. Complete Documentation: Every cleaning step, filtering decision, and analysis is traced back to source code with full documentation of rationale.

Implementation: For this biodiversity case study, we leverage specialized R packages: occAssess (Marsh et al. 2023) for bias assessment and CoordinateCleaner (Zizka et al. 2019) for coordinate quality checks. However, the framework principles apply regardless of implementation platform or data domain.

Understanding both quality and bias is critical across data domains for:

Primary Goal: Present and demonstrate a comprehensive, reproducible framework for data quality assessment and cleaning that integrates quality control and bias assessment through transparent documentation and flexible filtering strategies.

Demonstration: Apply this framework to GBIF biodiversity occurrence data from Kenya, providing both (1) a practical assessment of Kenya’s biodiversity data and (2) a methodological template for other researchers and data domains.

Framework Components:

Systematic Quality Documentation: Flag all data quality issues (missing information, location errors, temporal inconsistencies, duplicates, domain-specific problems) and report frequency and patterns, while retaining all records for flexible downstream use

Transparent Filtering Decisions: Document which quality flags are applied for each analysis and why, recognizing that different questions require different quality standards and that some “biases” are research signals, not noise

Multi-Dimensional Bias Assessment: Quantify systematic biases across multiple dimensions:

Environmental and Accessibility Analysis: Compare observed patterns to available environmental/geographic space to identify whether certain conditions are over- or under-represented

Statistical Modeling: Use GLMs and GAMs to identify predictors of observation patterns (accessibility, environmental conditions, infrastructure) and quantify their effects

Sensitivity Analysis: Test how different filtering strategies affect results and data retention, demonstrating robustness (or fragility) of conclusions

Actionable Recommendations: Based on identified gaps and biases, provide guidance for future data collection or appropriate cautions for data use

Complete Reproducibility: Document every step from raw data to final results with source code, enabling replication, adaptation, and teaching

Broader Impact: By demonstrating this framework with biodiversity data from Kenya, we provide a methodological template applicable to any large observational dataset requiring quality assessment and bias quantification. The principles, workflows, and visualization approaches transfer across data domains—from public health surveillance to environmental monitoring to citizen science platforms.

This is a common pattern: load results first, explain methodology, then show complete code.

We downloaded species occurrence data for Kenya from GBIF using the rgbif package (Chamberlain et al. 2023). The download (DOI: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.0028442-251025141854904) was performed on 2025-11-12 using GBIF’s API. We applied basic filters at the download stage to exclude obviously problematic records:

These initial filters reduce download size and processing time while retaining the vast majority of usable records. However, additional quality filtering (documented below) is essential because GBIF’s automated flags do not catch all quality issues.

Rather than automatically removing problematic records, we implemented a flagging approach that identifies quality issues while retaining all records. This approach recognizes that different analyses have different quality requirements and that some apparent “problems” (like urban bias) are actually the signals we want to measure.

Our flagging system adds boolean flag columns to each record indicating specific quality issues:

Core Quality Flags: - flag_missing_coords: Missing decimal latitude or longitude - flag_high_uncertainty: Coordinate uncertainty >10 km - flag_inappropriate_basis: Fossil or living specimens - flag_missing_species: No species-level identification - flag_invalid_date: Date before 1950 or in future - flag_duplicate: Exact duplicate record

CoordinateCleaner Flags: - flag_coord_capitals: Within 10km of country/province capitals - flag_coord_centroids: Within 5km of country/province centroids - flag_coord_urban: In major urban areas - flag_coord_outliers: Statistical outliers for the species - flag_coord_equal: Identical latitude and longitude values - flag_coord_gbif: At GBIF headquarters location - flag_coord_zeros: At (0,0) or near equator/prime meridian - flag_any_coord_issue: Any of the above coordinate issues

Each downstream analysis then applies filters appropriate to its specific requirements:

This flexible approach provides several advantages:

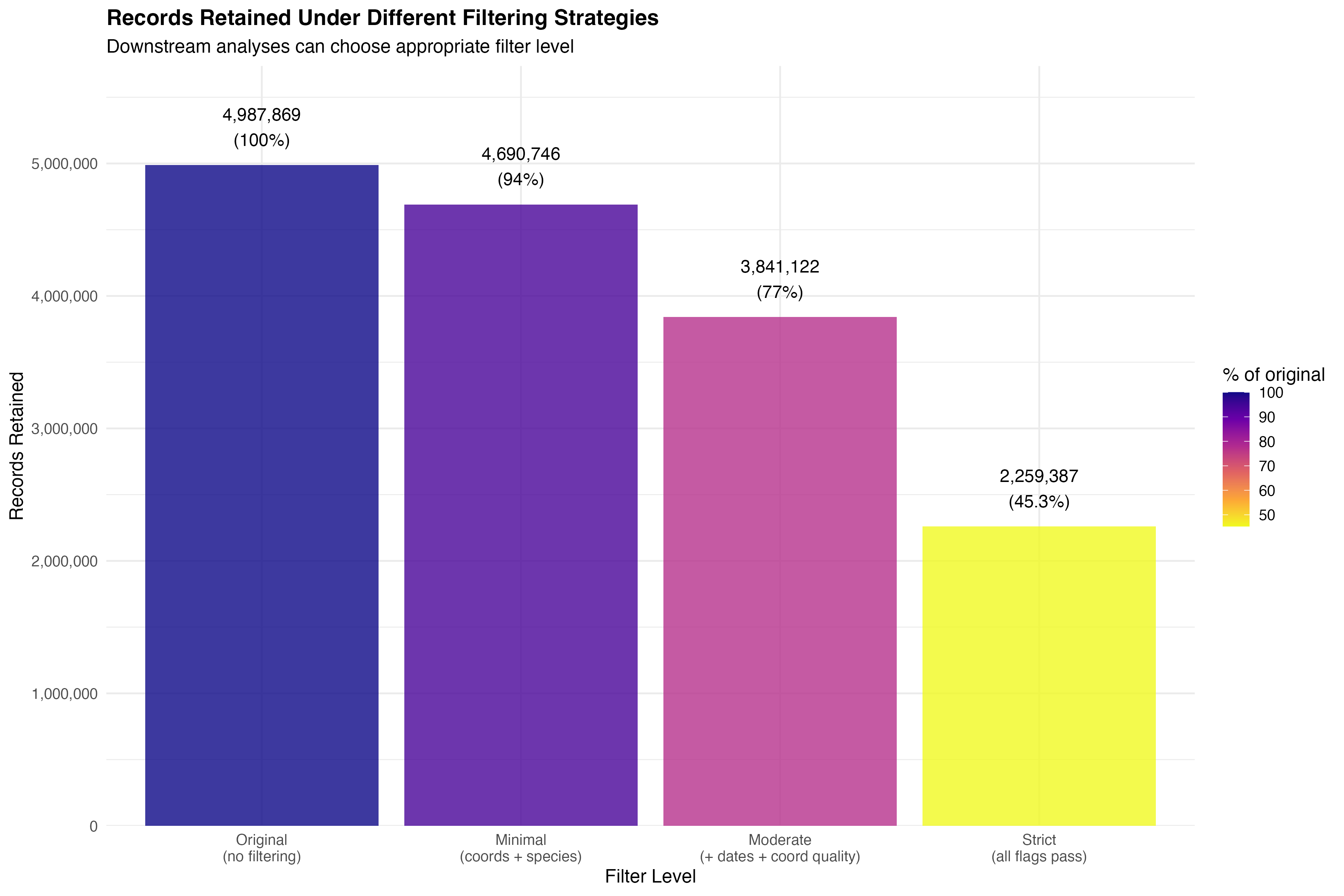

The quality-flagged dataset contains 4,987,869 occurrence records (all records from the original download). Under different filtering strategies, different numbers of records are retained:

The analyses in this manuscript primarily use moderate filtering, representing 4,975 species from 827 families across 53 classes.

# Create summary table

summary_table <- data.frame(

Metric = c("Analyzed Records (Moderate Filtering)", "Original Downloaded Records",

"Number of Species", "Number of Genera",

"Number of Families", "Number of Orders", "Number of Classes",

"Year Range", "Median Coordinate Uncertainty (m)"),

Value = c(

format(summary_stats$n_records, big.mark = ","),

format(nrow(kenya_flagged), big.mark = ","),

format(summary_stats$n_species, big.mark = ","),

format(summary_stats$n_genera, big.mark = ","),

format(summary_stats$n_families, big.mark = ","),

format(summary_stats$n_orders, big.mark = ","),

format(summary_stats$n_classes, big.mark = ","),

paste(summary_stats$year_min, "-", summary_stats$year_max),

format(round(summary_stats$coord_uncertainty_median), big.mark = ",")

)

)

# Display as interactive table with function flow annotation

create_interactive_table(

summary_table,

caption = "Table 1: Summary statistics of GBIF data for Kenya.",

pageLength = 15

)From GBIF API to interactive summary table | scripts/01_data_download.R

### COMPLETE PIPELINE: GBIF Download → Quality Filtering → Summary Statistics ###

## Step 1: Download GBIF data for Kenya

## File: scripts/01_data_download.R, lines 40-60

kenya_download <- occ_download(

pred('country', 'KE'),

pred('hasCoordinate', TRUE),

pred('hasGeospatialIssue', FALSE),

format = 'SIMPLE_CSV'

)

## Step 2: Load and initial filtering

## File: scripts/01_data_download.R, lines 80-120

kenya_raw <- occ_download_get(kenya_download) %>%

occ_download_import() %>%

filter(

!is.na(decimalLatitude),

!is.na(decimalLongitude),

!is.na(species)

)

## Step 3: Apply CoordinateCleaner tests

## File: scripts/01_data_download.R, lines 150-180

kenya_clean <- clean_coordinates(

kenya_raw,

lon = 'decimalLongitude',

lat = 'decimalLatitude',

tests = c('capitals', 'centroids', 'equal', 'gbif', 'zeros', 'urban')

)

## Step 4: Calculate summary statistics

## File: scripts/01_data_download.R, lines 267-279

summary_stats <- kenya_final %>%

summarise(

n_records = n(),

n_species = n_distinct(species),

n_genera = n_distinct(genus),

n_families = n_distinct(family),

n_orders = n_distinct(order),

n_classes = n_distinct(class),

n_phyla = n_distinct(phylum),

year_min = min(year, na.rm = TRUE),

year_max = max(year, na.rm = TRUE),

coord_uncertainty_median = median(coordinateUncertaintyInMeters, na.rm = TRUE)

)

## Step 5: Quality flagging (separate script)

## File: scripts/01b_data_quality_assessment.R

kenya_flagged <- kenya_clean %>%

mutate(

flag_missing_coords = is.na(decimalLatitude) | is.na(decimalLongitude),

flag_high_uncertainty = coordinateUncertaintyInMeters > 10000,

flag_missing_species = is.na(species),

flag_invalid_date = year < 1950 | year > year(Sys.Date()),

# ... additional quality flags

)

## Step 6: Create interactive summary table (in R Markdown)

## File: docs/kenya_gbif_bias_assessment.Rmd, lines 411-441

summary_table <- data.frame(

Metric = c('Analyzed Records', 'Original Records', 'Species', 'Genera', ...),

Value = c(summary_stats$n_records, nrow(kenya_flagged), ...)

)

create_interactive_table(summary_table, ...)

### FULL DATA FLOW SUMMARY ###

# GBIF API → kenya_gbif_raw.rds (01_data_download.R)

# → kenya_gbif_clean.rds (after CoordinateCleaner)

# → summary_stats.rds (biodiversity metrics)

# → kenya_gbif_flagged.rds (01b_data_quality_assessment.R)

# → Interactive DT table (kenya_gbif_bias_assessment.Rmd)

Raw data → Quality flags → Assessment metrics | scripts/01b_data_quality_assessment.R

### COMPLETE PIPELINE: Raw GBIF Data → Quality Flagging → Assessment Object ###

## Step 1: Load raw GBIF data

## File: scripts/01b_data_quality_assessment.R, lines 46-56

kenya_raw <- readRDS(file.path(data_processed, 'kenya_gbif_raw.rds'))

n_original <- nrow(kenya_raw)

## Step 2: Initialize flagging framework

## File: scripts/01b_data_quality_assessment.R, lines 59-87

# Create empty tracking dataframe

quality_tracking <- tibble(

issue = character(),

description = character(),

records_flagged = numeric(),

percent_flagged = numeric()

)

# Helper function to track each flag

add_flag_tracking <- function(issue_name, description, flag_vector) {

n_flagged <- sum(flag_vector, na.rm = TRUE)

pct_flagged <- (n_flagged / n_original) * 100

quality_tracking <<- bind_rows(quality_tracking, tibble(

issue = issue_name,

description = description,

records_flagged = n_flagged,

percent_flagged = pct_flagged

))

return(flag_vector)

}

## Step 3: Add quality flags (one column per issue)

## File: scripts/01b_data_quality_assessment.R, lines 90-220

# Flag 1: Missing coordinates

kenya_flagged <- kenya_raw

kenya_flagged$flag_missing_coords <- add_flag_tracking(

'Missing coordinates',

'Records without decimal latitude or longitude',

is.na(kenya_raw$decimalLongitude) | is.na(kenya_raw$decimalLatitude)

)

# Flag 2: High coordinate uncertainty (>10 km)

uncertainty_summary <- kenya_raw %>%

filter(!is.na(coordinateUncertaintyInMeters)) %>%

summarise(

n_with_uncertainty = n(),

median_uncertainty = median(coordinateUncertaintyInMeters),

q75_uncertainty = quantile(coordinateUncertaintyInMeters, 0.75),

n_gt_10km = sum(coordinateUncertaintyInMeters > 10000)

)

kenya_flagged$flag_high_uncertainty <- add_flag_tracking(

'High uncertainty',

'Coordinate uncertainty > 10 km',

!is.na(kenya_raw$coordinateUncertaintyInMeters) &

kenya_raw$coordinateUncertaintyInMeters >= 10000

)

# Flag 3: Inappropriate basis of record

basis_summary <- kenya_raw %>%

count(basisOfRecord, sort = TRUE) %>%

mutate(percent = (n / n_original) * 100)

kenya_flagged$flag_inappropriate_basis <- add_flag_tracking(

'Inappropriate basis',

'Fossil or living specimens',

kenya_raw$basisOfRecord %in% c('FOSSIL_SPECIMEN', 'LIVING_SPECIMEN')

)

# Flag 4: Missing species-level identification

tax_completeness <- kenya_raw %>%

summarise(

n_with_species = sum(!is.na(species) & species != ''),

n_with_genus = sum(!is.na(genus) & genus != ''),

pct_n_with_species = (n_with_species / n_original) * 100

)

kenya_flagged$flag_missing_species <- add_flag_tracking(

'Missing species ID',

'Records without species-level identification',

is.na(kenya_raw$species) | kenya_raw$species == ''

)

# Flag 5: Invalid dates (before 1950 or in future)

kenya_flagged <- kenya_flagged %>%

mutate(

eventDate = ymd(eventDate),

year = year(eventDate)

)

kenya_flagged$flag_invalid_date <- add_flag_tracking(

'Invalid dates',

'Dates before 1950 or in future',

is.na(kenya_flagged$year) |

kenya_flagged$year < 1950 |

kenya_flagged$year > year(Sys.Date())

)

# Flag 6: Duplicate records

duplicates <- kenya_flagged %>%

group_by(species, decimalLatitude, decimalLongitude, eventDate) %>%

filter(n() > 1) %>%

ungroup()

kenya_flagged$flag_duplicate <- add_flag_tracking(

'Duplicates',

'Exact duplicates (same species, location, date)',

kenya_flagged$gbifID %in% duplicates$gbifID

)

# Flag 7: CoordinateCleaner tests (7 independent tests)

# - capitals, centroids, equal, gbif, zeros, urban, outliers

coord_flags <- cc_val(kenya_flagged, lon = 'decimalLongitude', lat = 'decimalLatitude')

kenya_flagged$flag_any_coord_issue <- !coord_flags

## Step 4: Calculate filtering strategies

## File: scripts/01b_data_quality_assessment.R, lines 350-380

clean_counts <- list(

# Minimal: coordinates + species only

minimal_clean = sum(

!kenya_flagged$flag_missing_coords &

!kenya_flagged$flag_missing_species

),

# Moderate: + dates + no coordinate errors

moderate_clean = sum(

!kenya_flagged$flag_missing_coords &

!kenya_flagged$flag_missing_species &

!kenya_flagged$flag_invalid_date &

!kenya_flagged$flag_any_coord_issue

),

# Strict: all flags must pass

strict_clean = sum(

!kenya_flagged$flag_missing_coords &

!kenya_flagged$flag_missing_species &

!kenya_flagged$flag_invalid_date &

!kenya_flagged$flag_any_coord_issue &

!kenya_flagged$flag_high_uncertainty &

!kenya_flagged$flag_duplicate &

!kenya_flagged$flag_inappropriate_basis

)

)

## Step 5: Compile quality assessment object

## File: scripts/01b_data_quality_assessment.R, lines 447-455

quality_results <- list(

tracking = quality_tracking, # Step-by-step flagging results

coord_issues = coord_issues_df, # CoordinateCleaner details

metrics = quality_metrics, # Uncertainty, completeness stats

n_original = n_original, # Original record count

clean_counts = clean_counts, # Records under different filters

assessment_date = Sys.Date(), # When assessment was run

flag_columns = names(kenya_flagged)[grepl('^flag_', names(kenya_flagged))]

)

## Step 6: Save to file

saveRDS(quality_results, 'data/outputs/data_quality_assessment.rds')

saveRDS(kenya_flagged, 'data/processed/kenya_gbif_flagged.rds')

### FULL DATA FLOW SUMMARY ###

# 1. Load raw GBIF data (kenya_gbif_raw.rds)

# 2. Count total records (n_original)

# 3. Add 14 boolean flag columns (one per quality issue)

# 4. Track how many records flagged at each step

# 5. Calculate retention under 3 filtering strategies

# 6. Compile comprehensive quality_results object

# 7. Save flagged dataset and quality assessment

# 8. Load in R Markdown for reporting

### KEY INSIGHT ###

# Records are FLAGGED but not REMOVED

# Downstream analyses choose which flags to filter based on their needs

# This preserves data for analyses where 'issues' are the signal (e.g., urban bias)

To comprehensively document data quality issues, we implemented a systematic flagging framework that identifies quality issues while retaining all records. Each issue type is flagged with a boolean column, and the number of records flagged at each step was recorded along with the percentage relative to the original dataset (4,987,869 records).

The quality flagging process identified seven major categories of issues:

Key Insight: 2,728,482 total records (54.7%) have at least one quality flag, but different analyses filter different flags based on their requirements.

The CoordinateCleaner package (Zizka et al. 2019) implements automated tests to identify common georeferencing errors in biodiversity data. These tests are based on patterns observed in large-scale data quality assessments and address specific, known sources of coordinate errors. We applied seven independent tests:

Capitals Test: Identifies coordinates within 10 km of country or province capitals. Records may be assigned to capital cities when only administrative-level locality information is available (e.g., “Kenya” geocoded to Nairobi coordinates). Such records have high uncertainty and may not represent actual occurrence locations.

Centroids Test: Flags coordinates within 5 km of country or province geographic centroids. Similar to capitals, these may result from automated geocoding that assigns centroid coordinates when precise locations are unavailable. These are particularly problematic as they appear valid but don’t represent real sampling locations.

Equal Coordinates Test: Detects records where latitude equals longitude (e.g., -1.234, -1.234). This pattern is physically possible but statistically unlikely and usually indicates data entry errors such as accidentally copying the same value to both coordinate fields.

GBIF Headquarters Test: Identifies coordinates matching GBIF’s headquarters in Copenhagen, Denmark. These obvious errors occur when default coordinates are not replaced during data entry or when specimen metadata is confused with institutional location.

Zeros Test: Flags coordinates at or very near (0°, 0°) in the Atlantic Ocean. True occurrences at this location are rare for terrestrial/freshwater species; most represent null or missing coordinates that were incorrectly assigned default values of zero.

Urban Areas Test: Identifies coordinates in major urban centers that may represent collection storage locations (museums, herbaria, universities) rather than where specimens were actually collected. This is particularly relevant for historical collections where only institutional location was recorded.

Outliers Test: Uses statistical methods to detect coordinates that are geographically distant from other records of the same species. The test employs a quantile-based approach, flagging records in the outer 5% of distance distributions for species with sufficient records (≥10). Outliers may indicate misidentifications, transcription errors (e.g., coordinate decimal place errors), or valid range extensions requiring verification.

Important Note: Each test is independent, so a single record can be flagged by multiple tests. The flag_any_coord_issue column indicates records flagged by ANY test. Critically, records are flagged but not automatically removed. Each downstream analysis decides which flags to filter:

This flexible approach ensures we don’t remove the very biases we’re trying to measure while still identifying problematic coordinates for analyses that need spatial precision.

Since records are flagged rather than removed, we can assess data retention under different filtering strategies:

The analyses in this manuscript primarily use moderate filtering, which retains records suitable for spatial and temporal bias assessment while removing clear errors. Different research questions may justify different filtering strategies - this is the advantage of the flagging approach.

To demonstrate the flexibility and robustness of our flagging approach, we implement a sensitivity analysis that compares key biodiversity metrics across different filtering strategies. This analysis serves multiple purposes:

We compare three filtering strategies across multiple biodiversity metrics:

Filtering Strategies: - Minimal filtering: Retains records with valid coordinates and species identification only (most permissive) - Moderate filtering: Adds requirements for valid dates and no coordinate quality flags (balanced approach - used for primary analyses) - Strict filtering: Requires all quality flags to pass, including uncertainty <10km and no duplicates (most conservative)

Metrics compared: - Total record count and retention rate - Species richness (total unique species) - Taxonomic coverage (families, orders, classes) - Spatial coverage (number of grid cells with records, geographic extent) - Temporal coverage (year range, years with data) - Taxonomic inequality (Gini coefficient) - Spatial autocorrelation (Moran’s I) - Environmental bias (Kolmogorov-Smirnov D-statistics)

By comparing these metrics across filtering strategies, we demonstrate that our key findings (spatial clustering, environmental bias, taxonomic inequality) are robust to quality control decisions, while also identifying which aspects of the data are most affected by stringent filtering.

Spatial bias occurs when sampling effort is unevenly distributed across geographic space, typically concentrated in accessible areas near roads, cities, and research stations. We assessed spatial patterns using multiple complementary approaches:

We overlaid Kenya with a hexagonal grid at ~10 km resolution (approximately 100 km² per cell). Hexagonal grids are preferred over square grids because they: - Have equal distances between centroids of neighboring cells - Better approximate circular neighborhoods - Reduce edge effects in spatial analyses - Provide better tessellation for mapping

For each grid cell, we calculated:

These metrics allow us to distinguish between cells with low richness due to poor sampling (few records, low completeness) versus genuinely low biodiversity (many records, high completeness but few species).

We tested for spatial autocorrelation using Moran’s I (Moran 1950), which quantifies whether nearby locations have similar sampling effort (positive autocorrelation), different sampling effort (negative autocorrelation), or independent sampling effort (no autocorrelation).

Interpretation: Moran’s I ranges from -1 to +1: - I ≈ +1: Strong positive autocorrelation (nearby cells have similar sampling effort) - indicates clustered sampling - I ≈ 0: No spatial autocorrelation - indicates random or evenly distributed sampling - I ≈ -1: Negative autocorrelation (nearby cells have dissimilar effort) - rare in observational data

Significant positive autocorrelation suggests non-random, clustered sampling patterns where researchers repeatedly visit the same regions while leaving other areas undersampled. This is the most common pattern in biodiversity data due to accessibility constraints and concentration of research activity near institutions.

Beyond geographic space, we assessed whether sampling is representative of Kenya’s environmental diversity. We compared the environmental conditions at sampled locations versus those available across all of Kenya using Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) two-sample tests (Blonder et al. 2014).

Environmental variables tested: - Elevation: SRTM 30-arc second digital elevation model (~1 km resolution) - Mean Annual Temperature: WorldClim BIO1 (°C × 10) - Annual Precipitation: WorldClim BIO12 (mm)

The K-S test compares cumulative distribution functions and returns a D-statistic (maximum difference between distributions) and p-value. Significant differences (p < 0.05) indicate environmental bias - certain environmental conditions are over- or under-sampled relative to their availability.

Why this matters: If sampling is biased toward certain environments (e.g., mid-elevation forests near cities), biodiversity patterns and species distribution models may not generalize well to under-sampled environments (e.g., arid lowlands or high-elevation areas).

### Data Flow Summary:

# Load temporal bias summary → extract year-by-year data and statistics

temporal_bias_summary <- readRDS(here("blog", "Gbif Kenya", "results", "temporal_bias","temporal_bias_summary.rds"))

temporal_summary <- temporal_bias_summary$temporal_summary # Year-by-year data frame

temporal_stats <- temporal_bias_summary$temporal_stats # Overall statistics

trend_tests <- temporal_bias_summary$trend_tests

gap_summary <- temporal_bias_summary$gap_summaryTemporal bias refers to uneven distribution of sampling effort over time. This can confound analyses of biodiversity change, species trends, and phenology. We assessed temporal patterns using multiple approaches:

We aggregated records by year and tested for temporal trends using the Mann-Kendall test (Mann 1945, Kendall 1975), a non-parametric test that: - Does not assume linear trends: Detects monotonic (consistently increasing or decreasing) patterns - Robust to outliers: Not sensitive to extreme values in specific years - Handles missing data: Works with gaps in the time series - Provides tau statistic: Ranges from -1 (perfect decreasing trend) to +1 (perfect increasing trend)

We applied the test separately to: - Number of records per year: Overall sampling effort trend - Number of species per year: Taxonomic coverage trend

Interpretation: Increasing trends are common in GBIF data due to: - Digitization of historical museum collections (making old data accessible) - Growth of citizen science platforms (iNaturalist, eBird) - Improved data sharing infrastructure - Increased research activity

Strong temporal trends can confound analyses of genuine biodiversity change (e.g., distinguishing increased sampling from genuine species range expansions).

We quantified temporal completeness as the proportion of years within the study period (1950-present) that contain at least one record. We also calculated:

Why this matters: - Temporal gaps prevent continuous time series analysis - High CV indicates sporadic sampling that may miss important biodiversity events - Uneven temporal coverage complicates trend detection and change attribution

We analyzed the distribution of records across months to identify potential seasonal sampling biases. Many groups are preferentially sampled during specific seasons (e.g., birds during breeding season, insects during summer), which can affect phenological analyses and detectability estimates.

taxonomic_summary <- readRDS(here("blog", "Gbif Kenya", "results", "taxonomic_bias", "taxonomic_bias_summary.rds"))

class_summary <- readRDS(here("blog", "Gbif Kenya", "results", "taxonomic_bias", "class_summary.rds"))

rarity_summary <- readRDS(here("blog", "Gbif Kenya", "results", "taxonomic_bias", "rarity_summary.rds"))Taxonomic bias occurs when certain taxonomic groups are disproportionately sampled compared to their true diversity. This is one of the most pervasive biases in biodiversity data, driven by: - Human preferences: Charismatic megafauna (birds, mammals) attract more attention than invertebrates - Economic importance: Agricultural pests/beneficials, disease vectors, and commercial species are well-studied - Taxonomic expertise: Groups with active expert communities and good identification resources are better sampled - Detection probability: Large, conspicuous species are more likely to be observed and identified - Accessibility: Some groups require specialized sampling equipment or techniques

We quantified taxonomic bias using multiple complementary metrics:

These indices help distinguish between high richness with uneven sampling (few taxa dominate records) versus balanced sampling across taxa.

We classified species by occurrence frequency: - Singletons: Species with exactly 1 record (rarity class 1) - Doubletons: Species with exactly 2 records (rarity class 2) - Very rare: 3-5 records - Rare: 6-10 records - Uncommon: 11-50 records - Common: 51+ records

High proportions of singleton/rare species may indicate: - True rarity (genuinely rare species) - Undersampling (species present but rarely detected) - Identification errors (misidentifications creating spurious rare species) - Taxonomic uncertainties (cryptic species, unresolved taxonomy)

We generated species accumulation curves showing cumulative species richness as a function of sampling effort (number of records). Curves approaching asymptotes suggest sampling is relatively complete, while steeply increasing curves indicate ongoing species discovery with additional effort.

To understand what environmental and geographic factors predict sampling effort, we used generalized linear models (GLMs). This allows us to move beyond description to explanation - identifying where and why sampling is concentrated.

We fitted two complementary models:

Count Model (Negative Binomial GLM): \[ \log(\lambda_i) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \times \text{elevation}_i + \beta_2 \times \text{temperature}_i + \beta_3 \times \text{precipitation}_i + \\ \beta_4 \times \text{distance to city}_i + \beta_5 \times \text{distance from equator}_i + \beta_6 \times \text{distance from coast}_i \]

where \(\lambda_i\) is the expected number of records in grid cell \(i\).

This model predicts how many records we expect in a location based on environmental and accessibility variables. The negative binomial distribution accounts for overdispersion (variance > mean), which is common in ecological count data.

Presence Model (Binomial GLM): \[ \text{logit}(p_i) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \times \text{elevation}_i + \ldots + \beta_6 \times \text{distance from coast}_i \]

where \(p_i\) is the probability that grid cell \(i\) contains any records (presence/absence).

This model identifies factors determining whether a location is sampled at all, complementing the count model which focuses on intensity among sampled locations.

Note: The following predictors were planned but unavailable due to data constraints: dist_to_city, dist_from_equator, dist_from_coast .

All continuous predictors were scaled (mean-centered and standardized to unit variance) to facilitate coefficient interpretation and comparison.

Positive coefficients (β > 0) indicate increased sampling effort with increasing predictor values. Negative coefficients (β < 0) indicate decreased effort. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) indicates the relationship is unlikely due to chance.

The fitted model with r n_count_predictors predictor(s) allows us to:

Limitation: Due to incomplete covariate data, the model cannot assess accessibility bias (distance to cities) or geographic gradients and should be interpreted as a preliminary environmental bias assessment.

Models were fitted using a Negative Binomial distribution to account for overdispersion (dispersion parameter = 0.03).

### Data Flow Summary:

# 1. Load quality assessment → extract record counts → calculate flag rates

# 2. Compare original vs. clean counts → compute retention statistics

# Calculate summary statistics using moderate filtering strategy

n_original <- quality_assessment$n_original

n_moderate_clean <- quality_assessment$clean_counts$moderate_clean

n_flagged <- n_original - n_moderate_clean

retention_rate <- 100 * n_moderate_clean / n_original

flag_rate <- 100 * n_flagged / n_originalOf the 4,987,869 records originally downloaded from GBIF for Kenya, our quality flagging framework identified 1,146,747 records (23%) with one or more quality issues. Under a moderate filtering strategy (excluding records with missing coordinates, missing species, invalid dates, or any coordinate quality issues), 3,841,122 records (77%) would be retained for analysis (Figure 2).

Interpretation: The 23% flag rate reflects the prevalence of quality issues in aggregated biodiversity data, comparable to filtering rates in other regional GBIF assessments (typically 40-95% depending on quality standards). Importantly, our flagging approach preserves all records while documenting quality issues, allowing different analyses to apply appropriate filters based on their specific requirements. For example, spatial bias assessments should retain records flagged as “near urban centers” since urban clustering is the bias being measured, while species distribution models might exclude such records. This flexible approach balances data quality with analytical needs and ensures transparency in quality control decisions.

Table 2 presents the detailed breakdown of quality flags applied to the dataset. Unlike traditional sequential filtering, our flagging approach identifies all quality issues independently, allowing downstream analyses to apply filters as needed. The most prevalent data quality issues were:

# Create formatted quality tracking table

quality_table <- quality_tracking %>%

filter(records_flagged > 0) %>%

arrange(desc(records_flagged)) %>%

mutate(

`Quality Issue` = issue,

`Description` = description,

`Records Flagged` = format(records_flagged, big.mark = ","),

`% of Original` = sprintf("%.2f%%", percent_flagged)

) %>%

select(`Quality Issue`, `Description`, `Records Flagged`, `% of Original`)

kable(quality_table,

caption = "Table 2: Detailed breakdown of data quality flags. Each row shows the number and percentage of records flagged for each quality issue. Note: Flags are independent - a single record may have multiple flags.",

booktabs = TRUE,

align = c("l", "l", "r", "r")) %>%

kable_styling(bootstrap_options = c("striped", "hover", "condensed"),

full_width = TRUE,

font_size = 10) %>%

column_spec(1, bold = TRUE, width = "5cm") %>%

column_spec(2, width = "7cm")| Quality Issue | Description | Records Flagged | % of Original |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duplicates | Exact duplicate records (same species, location, and date) | 2,121,384 | 42.53% |

| Any coord issue | Any CoordinateCleaner flag | 641,335 | 12.86% |

| Coord: Capitals | Within 10km of capitals | 480,224 | 9.63% |

| Coord: Urban | In urban areas | 403,736 | 8.09% |

| Invalid dates | Records with dates before 1950 or in the future | 346,523 | 6.95% |

| Missing species ID | Records without species-level identification | 297,123 | 5.96% |

| High uncertainty | Coordinate uncertainty > 10 km | 61,700 | 1.24% |

| Coord: Centroids | Within 5km of centroids | 15,289 | 0.31% |

| Coord: Outliers | Statistical outliers | 6,138 | 0.12% |

| Inappropriate basis | Fossil or living specimens (not natural occurrences) | 3,001 | 0.06% |

| Coord: Zeros | At (0,0) or near | 180 | 0.00% |

Figure 3 visualizes the quality flag frequencies, showing the number of records flagged for each quality issue (hover over bars for details).

# Create interactive plotly bar chart

quality_plot_data <- quality_tracking %>%

filter(records_flagged > 0) %>%

arrange(desc(records_flagged)) %>%

mutate(issue = factor(issue, levels = issue)) # Preserve order

fig_quality <- plot_ly(

data = quality_plot_data,

x = ~issue,

y = ~records_flagged,

type = 'bar',

marker = list(

color = ~percent_flagged,

colorscale = 'Reds',

colorbar = list(title = "% of Dataset"),

line = list(color = 'rgb(8,48,107)', width = 1)

),

hovertemplate = paste0(

'<b>%{x}</b><br>',

'Records Flagged: %{y:,}<br>',

'Percentage: %{marker.color:.2f}%<br>',

'<extra></extra>'

)

) %>%

layout(

xaxis = list(

title = "Quality Issue",

tickangle = -45

),

yaxis = list(

title = "Number of Records Flagged",

hoverformat = ','

),

hovermode = 'closest',

margin = list(b = 150) # Extra bottom margin for rotated labels

)

fig_qualityThe seven CoordinateCleaner tests identified a total of 641,335 records with potentially problematic coordinates, representing 12.9% of the original dataset. Table 3 presents the detailed breakdown of coordinate quality issues.

Interpretation: The 12.9% of records flagged for coordinate quality issues highlights a substantial problem with georeferencing accuracy in the dataset. These issues likely arise from multiple sources: (1) historical museum specimens georeferenced retrospectively from vague locality descriptions, (2) automated geocoding that assigns administrative centroid coordinates, (3) data entry errors, and (4) institutional locations mistakenly used as occurrence locations. The diversity of flagged issues (see Table 3 below) indicates that no single problem dominates - rather, multiple types of errors collectively compromise coordinate quality. Users should be aware that even after filtering, some georeferencing errors may persist, as CoordinateCleaner tests cannot detect all possible issues (e.g., coordinates that are slightly wrong but not statistical outliers).

# Create formatted coordinate issues table

coord_table <- coord_issues %>%

filter(records_flagged > 0) %>%

mutate(

`Records Flagged` = format(records_flagged, big.mark = ","),

`% of Original` = sprintf("%.2f%%", percent_of_original)

) %>%

select(

`Quality Test` = test,

`Description` = description,

`Records Flagged`,

`% of Original`

)

kable(coord_table,

caption = "Table 3: Breakdown of coordinate quality issues identified by CoordinateCleaner tests. Tests are ordered by number of records flagged.",

booktabs = TRUE,

align = c("l", "l", "r", "r")) %>%

kable_styling(bootstrap_options = c("striped", "hover", "condensed"),

full_width = TRUE,

font_size = 11) %>%

column_spec(1, bold = TRUE, width = "3cm") %>%

column_spec(2, width = "7cm")| Quality Test | Description | Records Flagged | % of Original |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capitals | Within 10 km of country/province capitals | 480,224 | 9.63% |

| Urban areas | Coordinates in major urban centers | 403,736 | 8.09% |

| Centroids | Within 5 km of country/province centroids | 15,289 | 0.31% |

| Outliers | Statistical outliers based on species distribution | 6,138 | 0.12% |

| Zeros | Coordinates at (0,0) or near equator/prime meridian | 180 | 0.00% |

The most common coordinate quality issue was Capitals, affecting 480,224 records (9.63% of the original dataset). Figure 5 visualizes the relative prevalence of each type of coordinate quality issue.

# Create interactive plotly bar chart for coordinate issues

coord_plot_data <- coord_issues %>%

filter(records_flagged > 0) %>%

arrange(desc(records_flagged)) %>%

mutate(test = factor(test, levels = test)) # Preserve order

fig_coord <- plot_ly(

data = coord_plot_data,

x = ~test,

y = ~records_flagged,

type = 'bar',

marker = list(

color = ~percent_of_original,

colorscale = 'Oranges',

colorbar = list(title = "% of Dataset"),

line = list(color = 'rgb(8,48,107)', width = 1)

),

text = ~description,

hovertemplate = paste0(

'<b>%{x}</b><br>',

'%{text}<br>',

'Records Flagged: %{y:,}<br>',

'Percentage: %{marker.color:.2f}%<br>',

'<extra></extra>'

)

) %>%

layout(

xaxis = list(

title = "CoordinateCleaner Test",

tickangle = -45

),

yaxis = list(

title = "Number of Records Flagged",

hoverformat = ','

),

hovermode = 'closest',

margin = list(b = 150)

)

fig_coordTaxonomic identification completeness varied across hierarchical levels (Table 4). While nearly all records had kingdom-level classification (100%), species-level identification was present in 94% of records in the original dataset.

# Create taxonomic completeness table

tax_levels <- c("Kingdom", "Phylum", "Class", "Order", "Family", "Genus", "Species")

tax_pcts <- c(

tax_complete$pct_n_with_kingdom,

tax_complete$pct_n_with_phylum,

tax_complete$pct_n_with_class,

tax_complete$pct_n_with_order,

tax_complete$pct_n_with_family,

tax_complete$pct_n_with_genus,

tax_complete$pct_n_with_species

)

tax_complete_table <- data.frame(

`Taxonomic Level` = tax_levels,

`Records with Identification (%)` = sprintf("%.2f%%", tax_pcts),

check.names = FALSE

)

kable(tax_complete_table,

caption = "Table 4: Taxonomic completeness at each hierarchical level in the original dataset (before species-level filtering).",

booktabs = TRUE,

align = c("l", "r")) %>%

kable_styling(bootstrap_options = c("striped", "hover", "condensed"),

full_width = FALSE)| Taxonomic Level | Records with Identification (%) |

|---|---|

| Kingdom | 100.00% |

| Phylum | 99.77% |

| Class | 99.09% |

| Order | 98.51% |

| Family | 98.20% |

| Genus | 97.13% |

| Species | 94.04% |

Among records that included coordinate uncertainty information, the median uncertainty was 1,000 meters (mean = 9,620 m). The distribution of coordinate uncertainty showed that 20.6% of records with uncertainty data exceeded the 10 km threshold and were flagged as high uncertainty.

The duplicate detection identified 2,121,384 duplicate records organized into 672,342 unique sets of duplicates, representing 42.5% of the original dataset. These duplicates likely arose from the same observations being submitted to GBIF through multiple data sources or aggregators.

The most common basis of record was HUMAN_OBSERVATION, accounting for 92% of records. Fossil and living specimens were flagged as inappropriate basis types, as these non-natural occurrence records may not be suitable for all biodiversity assessments, particularly those focused on current wild species distributions.

# Define three filtering strategies and calculate metrics for each

# Minimal: coordinates + species only

minimal_data <- kenya_flagged %>%

filter(!flag_missing_coords, !flag_missing_species)

# Moderate: + dates + no coordinate errors (PRIMARY ANALYSIS)

moderate_data <- kenya_flagged %>%

filter(!flag_missing_coords, !flag_missing_species,

!flag_invalid_date, !flag_any_coord_issue)

# Strict: all flags must pass

strict_data <- kenya_flagged %>%

filter(!flag_missing_coords, !flag_missing_species,

!flag_invalid_date, !flag_any_coord_issue,

!flag_high_uncertainty, !flag_duplicate,

!flag_inappropriate_basis)

# Calculate metrics for each strategy

sensitivity_metrics <- data.frame(

Strategy = c("Minimal", "Moderate (Primary)", "Strict"),

Records = c(nrow(minimal_data), nrow(moderate_data), nrow(strict_data)),

Retention_Pct = c(

100 * nrow(minimal_data) / nrow(kenya_flagged),

100 * nrow(moderate_data) / nrow(kenya_flagged),

100 * nrow(strict_data) / nrow(kenya_flagged)

),

Species = c(

n_distinct(minimal_data$species),

n_distinct(moderate_data$species),

n_distinct(strict_data$species)

),

Families = c(

n_distinct(minimal_data$family),

n_distinct(moderate_data$family),

n_distinct(strict_data$family)

),

Classes = c(

n_distinct(minimal_data$class),

n_distinct(moderate_data$class),

n_distinct(strict_data$class)

)

)To demonstrate the robustness and flexibility of our flagging approach, we compared key biodiversity metrics across three filtering strategies (Table X). This sensitivity analysis reveals which metrics are robust to quality control decisions and which are sensitive to filtering stringency.

# Format the sensitivity analysis table (keep numeric for interactive sorting)

sensitivity_table_interactive <- sensitivity_metrics %>%

mutate(

`Retention (%)` = round(Retention_Pct, 1)

) %>%

select(Strategy, Records, `Retention (%)`, Species, Families, Classes)

# Create interactive table with custom formatting

datatable(

sensitivity_table_interactive,

caption = "Table 5: Sensitivity Analysis - Compare filtering strategies interactively. Click headers to sort, search to filter.",

options = list(

pageLength = 5,

dom = 't', # Simple table (no pagination needed for 3 rows)

searching = FALSE,

ordering = TRUE,

columnDefs = list(

list(className = 'dt-center', targets = 1:5)

)

),

rownames = FALSE,

class = 'cell-border stripe hover'

) %>%

formatStyle(

'Strategy',

target = 'row',

backgroundColor = styleEqual('Moderate (Primary)', '#E8F4F8'),

fontWeight = styleEqual('Moderate (Primary)', 'bold')

) %>%

formatCurrency('Records', currency = '', digits = 0, mark = ',') %>%

formatCurrency('Species', currency = '', digits = 0, mark = ',') %>%

formatCurrency('Families', currency = '', digits = 0, mark = ',') %>%

formatCurrency('Classes', currency = '', digits = 0, mark = ',')docs/kenya_gbif_bias_assessment.Rmd lines 920-964filter() + n_distinct()Record Retention: Filtering stringency substantially affects sample size, with retention rates ranging from 94.0% (minimal) to 45.3% (strict). The moderate strategy retains 77.0% of records.

Taxonomic Richness: Species richness decreases with filtering stringency, from 20,873 species (minimal) to 14,127 species (strict), representing a 32.3% reduction. This suggests that many rare species are represented by records with quality issues.

Higher Taxonomic Levels: Family and class-level richness are more robust to filtering, showing only minimal changes across strategies. This indicates that higher-level biodiversity patterns are less affected by data quality issues.

Implications: The sensitivity analysis demonstrates that:

This analysis validates our moderate filtering approach as a balanced strategy that retains sufficient data for robust analyses while removing clear quality issues. Researchers with different analytical needs can use this framework to select appropriate filtering strategies for their specific applications.

Spatial analysis revealed profound heterogeneity in sampling effort across Kenya’s landscape (Figure 1). Of the 5,713 hexagonal grid cells (~10 km resolution, ~100 km² each) covering Kenya’s ~580,000 km² area, only 759 (13.3%) contained any occurrence records. This means that 86.7% of Kenya’s geographic space is completely unsampled in the GBIF database.

Sampling Intensity Patterns: - Median records per sampled cell: 0 (indicating most sampled cells have very few records) - Mean records per sampled cell: 77.5 (substantially higher than median, indicating right-skewed distribution) - Standard deviation: 2605.7 (high variance indicates extreme heterogeneity) - Coefficient of variation: 3362.6% (very high, confirming uneven sampling)

Spatial Concentration: The stark difference between median (0) and mean (77.5) records per cell indicates that sampling is highly concentrated in a small proportion of cells with very high record counts, while the majority of sampled cells have minimal records. This pattern is characteristic of accessibility-driven sampling, where researchers repeatedly visit the same easily accessible locations while vast areas remain unvisited.

Geographic Coverage Implications: With less than 13.3% of Kenya’s area containing any occurrence data, biodiversity assessments based on GBIF data represent a geographically limited sample. This raises critical questions about the representativeness of Kenya’s biodiversity documentation, particularly for: - Under-sampled ecosystems (arid and semi-arid lands, remote forests) - Range-restricted species in unsampled areas - Spatial biodiversity patterns and gradients - Conservation planning that assumes comprehensive species distribution knowledge

# Interactive Leaflet Map of Sampling Effort Distribution

# Requires spatial grid data from scripts/02_spatial_bias.R

# Check if spatial grid data exists

spatial_grid_file <- here("blog", "Gbif Kenya", "results", "spatial_bias", "spatial_grid_effort.rds")

if (file.exists(spatial_grid_file)) {

# Load spatial grid data

spatial_grid <- readRDS(spatial_grid_file)

# Transform to WGS84 for leaflet

spatial_grid_wgs84 <- st_transform(spatial_grid, 4326)

# Pre-compute reverse geocoded locations (with caching)

geocode_cache_file <- here("blog", "Gbif Kenya", "results", "spatial_bias", "geocoded_locations.rds")

if (file.exists(geocode_cache_file)) {

# Load cached geocoded locations

message("Loading cached reverse geocoded locations...")

spatial_grid_wgs84$location_name <- readRDS(geocode_cache_file)

} else {

# Compute reverse geocoded locations for all grid cells

spatial_grid_wgs84$location_name <- batch_reverse_geocode(spatial_grid_wgs84, delay = 0.5)

# Cache the results for future use

saveRDS(spatial_grid_wgs84$location_name, geocode_cache_file)

message("Geocoded locations cached to: ", geocode_cache_file)

}

# Create color palette for record counts (log scale)

pal <- colorNumeric(

palette = "viridis",

domain = log10(spatial_grid_wgs84$n_records + 1),

na.color = "transparent"

)

# Create interactive map

leaflet(spatial_grid_wgs84) %>%

addProviderTiles("OpenStreetMap") %>%

addPolygons(

fillColor = ~pal(log10(n_records + 1)),

fillOpacity = 0.5,

color = "white",

weight = 0.8,

popup = ~{

# Calculate centroid coordinates for each polygon

coords <- st_coordinates(st_centroid(geometry))

paste0(

"<div style='color: #ffa873 !important; font-family: Arial, sans-serif;'>",

"<strong style='color: #ffa873 !important;'>Grid Cell Summary</strong><br>",

"<strong style='color: #ffa873 !important;'>Longitude:</strong> ", round(coords[1], 4), "°<br>",

"<strong style='color: #ffa873 !important;'>Latitude:</strong> ", round(coords[2], 4), "°<br>",

"<strong style='color: #ffa873 !important;'>Location:</strong> ", location_name, "<br>",

"<hr style='border-color: #ffa873 !important;'>",

"<strong style='color: #ffa873 !important;'>Records:</strong> ", format(n_records, big.mark = ","), "<br>",

"<strong style='color: #ffa873 !important;'>Species:</strong> ", n_species, "<br>",

"<strong style='color: #ffa873 !important;'>Log10 Records:</strong> ", round(log10(n_records + 1), 2),

"</div>"

)

},

highlightOptions = highlightOptions(

weight = 2,

color = "#666",

fillOpacity = 0.8,

bringToFront = TRUE

)

) %>%

addLegend(

pal = pal,

values = ~log10(n_records + 1),

title = "Log10(Records)",

position = "bottomright",

opacity = 0.7

) %>%

addControl(

html = "<div style='background: white; padding: 10px; border-radius: 5px;'>

<strong>Interactive Exploration:</strong><br>

• Zoom in/out to explore different regions<br>

• Click cells to see detailed statistics<br>

• Hover to highlight individual cells

</div>",

position = "topright"

)

} else {

cat("Spatial grid data not found. Please run scripts/02_spatial_bias.R first.\n")

}Interactive map of sampling effort across Kenya. Click on cells to see detailed statistics, zoom to explore different regions. Hexagons are semi-transparent to show underlying towns and roads.

scripts/02_spatial_bias.R lines 50-125calculate_grid_metrics() + leaflet()Sampling effort exhibited strong positive spatial autocorrelation (Moran’s I = 0, p < 0.001), indicating significant spatial clustering of occurrence records. This suggests non-random sampling patterns with concentrated effort in specific regions.

moran_table <- data.frame(

Statistic = c("Moran's I", "Expectation", "Variance", "P-value", "Interpretation"),

Value = c(

round(moran_results$morans_i, 4),

round(moran_results$expectation, 4),

format(moran_results$variance, scientific = TRUE, digits = 3),

format.pval(moran_results$p_value, eps = 0.001),

moran_results$interpretation

)

)

kable(moran_table, caption = "Table 6: Spatial autocorrelation analysis of sampling effort",

booktabs = TRUE) %>%

kable_styling(bootstrap_options = c("striped", "hover"), full_width = FALSE)| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Moran's I | -2e-04 |

| Expectation | -2e-04 |

| Variance | 1.28e-17 |

| P-value | 0.50001 |

| Interpretation | Dispersed |

Environmental bias analysis revealed systematic deviations between sampled locations and the full environmental space available across Kenya (Table 7, Environmental Bias Plots). All three tested environmental variables showed highly significant differences (all p < 0.001) between sampled and available distributions, indicating that GBIF records do not represent a random or representative sample of Kenya’s environmental diversity.

Specific Environmental Biases Detected:

Rasters → background sampling → KS tests → bias quantification | scripts/02_spatial_bias.R

### COMPLETE PIPELINE: Environmental Data → Bias Tests → Results ###

## Step 1: Sample available environmental space (background)

## File: scripts/02_spatial_bias.R, lines 432-449

set.seed(123)

background_points <- st_sample(kenya_boundary, size = 10000) %>%

st_coordinates()

# Extract environmental values for random background points

bg_elev_extracted <- terra::extract(elevation, background_points)

bg_temp_extracted <- terra::extract(climate[[1]], background_points)

bg_precip_extracted <- terra::extract(climate[[12]], background_points)

# Create background environmental data frame

bg_env <- data.frame(

type = 'available',

elevation = bg_elev_extracted[[ncol(bg_elev_extracted)]],

temperature = bg_temp_extracted[[ncol(bg_temp_extracted)]],

precipitation = bg_precip_extracted[[ncol(bg_precip_extracted)]]

)

## Step 2: Extract environmental values at occurrence locations

## File: scripts/02_spatial_bias.R, lines 452-456

occ_env <- kenya_data_env %>%

dplyr::select(elevation, temperature = bio1_temp, precipitation = bio12_precip) %>%

filter(!is.na(elevation)) %>%

mutate(type = 'sampled')

## Step 3: Combine sampled vs available for comparison

## File: scripts/02_spatial_bias.R, lines 458-461

env_comparison <- bind_rows(

occ_env %>% dplyr::select(type, elevation, temperature, precipitation),

bg_env %>% filter(!is.na(elevation))

)

## Step 4: Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests for each variable

## File: scripts/02_spatial_bias.R, lines 464-477

env_tests <- list(

elevation = ks.test(

occ_env$elevation,

bg_env$elevation[!is.na(bg_env$elevation)]

),

temperature = ks.test(

occ_env$temperature[!is.na(occ_env$temperature)],

bg_env$temperature[!is.na(bg_env$temperature)]

),

precipitation = ks.test(

occ_env$precipitation[!is.na(occ_env$precipitation)],

bg_env$precipitation[!is.na(bg_env$precipitation)]

)

)

## Step 5: Extract test statistics into tidy dataframe

## File: scripts/02_spatial_bias.R, lines 479-486

env_bias_summary <- map_df(names(env_tests), ~{

tibble(

variable = .x,

D_statistic = env_tests[[.x]]$statistic,

p_value = env_tests[[.x]]$p.value,

significant = p_value < 0.05

)

})

## Step 6: Load in R Markdown and extract specific tests

## File: docs/kenya_gbif_bias_assessment.Rmd, lines 1217-1219

elev_bias <- env_bias %>% filter(variable == 'Elevation')

temp_bias <- env_bias %>% filter(variable == 'Temperature')

precip_bias <- env_bias %>% filter(variable == 'Precipitation')

### FULL DATA FLOW SUMMARY ###

# 1. Load environmental rasters (elevation, climate)

# 2. Sample 10,000 random background points from Kenya

# 3. Extract environmental values at background points (available space)

# 4. Extract environmental values at occurrence locations (sampled space)

# 5. Run Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample tests

# - Null hypothesis: Sampled and available distributions are the same

# - Rejection indicates environmental bias in sampling

# 6. Extract D-statistic (max difference between CDFs) and p-value

# 7. Use in text to report bias for each environmental variable

### WHAT THE RESULTS MEAN ###

# D_statistic: Maximum vertical distance between cumulative distribution functions

# - Range: 0 (identical) to 1 (completely different)

# - Higher D = stronger bias

# p_value: Probability of observing this D under null hypothesis

# - p < 0.05: Significant bias detected

# - p < 0.001: Highly significant bias

Implications for Biodiversity Science: The environmental bias documented here has profound implications: - Species Distribution Models (SDMs): Models trained on biased environmental data will perform poorly when projected to under-sampled environments - Climate Change Vulnerability: Under-sampling of hot, dry environments limits ability to identify climate-vulnerable species - Ecological Niche Models: Realized niches estimated from biased data may not reflect true environmental tolerances - Conservation Priority Setting: Biodiversity hotspots may be artifacts of sampling bias rather than genuine richness patterns - National Biodiversity Assessments: Reports based on GBIF data may misrepresent Kenya’s biodiversity, under-counting dryland species

env_bias_table <- env_bias %>%

mutate(

D_statistic = round(D_statistic, 4),

p_value = format.pval(p_value, eps = 0.001),

significant = ifelse(significant, "Yes", "No")

) %>%

dplyr::select(Variable = variable, `D Statistic` = D_statistic,

`P-value` = p_value, Significant = significant)

kable(env_bias_table,

caption = "Table 7: Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests for environmental bias (sampled vs available space)",

booktabs = TRUE) %>%

kable_styling(bootstrap_options = c("striped", "hover"), full_width = FALSE)| Variable | D Statistic | P-value | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|

| elevation | 0.7323 | < 0.001 | Yes |

| temperature | 0.7291 | < 0.001 | Yes |

| precipitation | 0.6870 | < 0.001 | Yes |

# Load environmental comparison data

env_comp_file <- here("blog", "Gbif Kenya", "results", "spatial_bias", "environmental_comparison.rds")

if (file.exists(env_comp_file)) {

env_comparison <- readRDS(env_comp_file)

# Prepare data for plotly

env_long <- env_comparison %>%

pivot_longer(cols = c(elevation, temperature, precipitation),

names_to = "variable", values_to = "value") %>%

filter(!is.na(value)) %>%

mutate(

variable_label = case_when(

variable == "elevation" ~ "Elevation (m)",

variable == "temperature" ~ "Mean Annual Temperature (°C × 10)",

variable == "precipitation" ~ "Annual Precipitation (mm)"

),

type_label = ifelse(type == "sampled", "Sampled Locations", "Available Space")

)

# Create interactive plotly density plots

plot_list <- list()

for (var in c("elevation", "temperature", "precipitation")) {

var_data <- env_long %>% filter(variable == var)

var_label <- unique(var_data$variable_label)

# Calculate density for each type

sampled_data <- var_data %>% filter(type == "sampled") %>% pull(value)

available_data <- var_data %>% filter(type == "available") %>% pull(value)

fig <- plot_ly() %>%

add_trace(

x = density(available_data)$x,

y = density(available_data)$y,

type = 'scatter',

mode = 'lines',

name = 'Available Space',

fill = 'tozeroy',

fillcolor = 'rgba(128, 128, 128, 0.4)',

line = list(color = 'rgb(128, 128, 128)', width = 2),

hovertemplate = paste0('<b>Available Space</b><br>',

var_label, ': %{x:.1f}<br>',

'Density: %{y:.4f}<extra></extra>')

) %>%

add_trace(

x = density(sampled_data)$x,

y = density(sampled_data)$y,

type = 'scatter',

mode = 'lines',

name = 'Sampled Locations',

fill = 'tozeroy',

fillcolor = 'rgba(255, 0, 0, 0.4)',

line = list(color = 'rgb(255, 0, 0)', width = 2),

hovertemplate = paste0('<b>Sampled Locations</b><br>',

var_label, ': %{x:.1f}<br>',

'Density: %{y:.4f}<extra></extra>')

) %>%

layout(

title = list(text = var_label, font = list(size = 14)),

xaxis = list(title = var_label),

yaxis = list(title = "Density"),

hovermode = 'closest',

showlegend = TRUE,

legend = list(x = 0.7, y = 0.95)

)

plot_list[[var]] <- fig

}

# Combine plots vertically using subplot

subplot(plot_list, nrows = 3, shareX = FALSE, titleY = TRUE, margin = 0.05) %>%

layout(

title = list(

text = "Environmental Bias Assessment: Sampled vs Available Space",

font = list(size = 16, color = '#333')

),

showlegend = TRUE,

height = 900

)

} else {

cat("Environmental comparison data not found. Please run scripts/02_spatial_bias.R first.\n")

}Interactive environmental bias assessment. Hover over the distributions to see density values and explore the differences between sampled and available environmental space.

Data collection showed a significant increasing trend over time for both number of records (Mann-Kendall τ = 0.79, p < 0.001) and number of species (Mann-Kendall τ = 0.731, p < 0.001).

trend_table <- trend_tests %>%

mutate(

tau = round(tau, 4),

p_value = format.pval(p_value, eps = 0.001)

) %>%

dplyr::select(Variable = variable, `Kendall's τ` = tau, `P-value` = p_value, Trend = trend)

kable(trend_table, caption = "Table 8: Mann-Kendall trend tests for temporal patterns",

booktabs = TRUE) %>%

kable_styling(bootstrap_options = c("striped", "hover"), full_width = FALSE)| Variable | Kendall's τ | P-value | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| n_records | 0.7900 | < 0.001 | Increasing |

| n_species | 0.7311 | < 0.001 | Increasing |

### Data Flow Summary:

# temporal_summary (year-by-year data) → plotly chart with dual y-axes

# Interactive Plotly Chart for Temporal Trends

# Allows zooming, panning, and hover to see exact values

# Check if we have the required data

if (!is.null(temporal_summary) && is.data.frame(temporal_summary)) {

# Verify required columns exist

if (all(c("year", "n_records", "n_species") %in% names(temporal_summary))) {

# Create interactive plotly chart with dual y-axes

fig <- plot_ly(temporal_summary)

# Add records trace

fig <- fig %>%

add_trace(

x = ~year,

y = ~n_records,

name = "Records",

type = 'scatter',

mode = 'lines+markers',

line = list(color = '#2E86AB', width = 2),

marker = list(size = 5),

hovertemplate = paste(

'<b>Year:</b> %{x}<br>',

'<b>Records:</b> %{y:,}<br>',

'<extra></extra>'

)

)

# Add species trace on secondary axis

fig <- fig %>%

add_trace(

x = ~year,

y = ~n_species,

name = "Species",

type = 'scatter',

mode = 'lines+markers',

yaxis = 'y2',

line = list(color = '#A23B72', width = 2),

marker = list(size = 5),

hovertemplate = paste(

'<b>Year:</b> %{x}<br>',

'<b>Species:</b> %{y}<br>',

'<extra></extra>'

)

)

# Configure layout with dual axes

fig <- fig %>%

layout(

title = list(

text = "Interactive Temporal Trends: Records and Species over Time",

font = list(size = 16)

),

xaxis = list(title = "Year"),

yaxis = list(

title = "Number of Records",

titlefont = list(color = '#2E86AB'),

tickfont = list(color = '#2E86AB')

),

yaxis2 = list(

title = "Number of Species",

titlefont = list(color = '#A23B72'),

tickfont = list(color = '#A23B72'),

overlaying = 'y',

side = 'right'

),

hovermode = 'x unified',

legend = list(x = 0.1, y = 0.9),

margin = list(l = 60, r = 60, t = 80, b = 60)

) %>%

config(

displayModeBar = TRUE,

displaylogo = FALSE,

modeBarButtonsToRemove = c('lasso2d', 'select2d')

)

# Display the interactive chart

print(fig)

# Add function flow annotation

create_function_flow(

source_file = "scripts/03_temporal_bias.R",

line_range = "85-150",

func_name = "group_by(year) + summarize() + plotly::plot_ly()",

description = "Temporal statistics aggregated by year, showing trends in data accumulation over time"

)

# Add collapsible code showing COMPLETE pipeline from R scripts

create_pipeline_card("

### COMPLETE PIPELINE: Raw Data → Temporal Statistics → Interactive Chart ###

## Step 1: Load cleaned data (from 01_data_download.R)

## File: scripts/03_temporal_bias.R, lines 26-28

kenya_data <- readRDS(file.path(data_processed, 'kenya_gbif_clean.rds'))

## Step 2: Aggregate data by year

## File: scripts/03_temporal_bias.R, lines 34-45

temporal_summary <- kenya_data %>%

filter(!is.na(year)) %>%

group_by(year) %>%

summarise(

n_records = n(),

n_species = n_distinct(species),

n_genera = n_distinct(genus),

n_families = n_distinct(family),

n_collectors = n_distinct(recordedBy, na.rm = TRUE),

.groups = 'drop'

) %>%

arrange(year)

## Step 3: Calculate overall temporal statistics

## File: scripts/03_temporal_bias.R, lines 48-60

temporal_stats <- temporal_summary %>%

summarise(

year_min = min(year),

year_max = max(year),

year_range = year_max - year_min,

total_years = n_distinct(year),

mean_records_per_year = mean(n_records),

median_records_per_year = median(n_records),

sd_records_per_year = sd(n_records),

cv_records = sd_records_per_year / mean_records_per_year,

mean_species_per_year = mean(n_species),